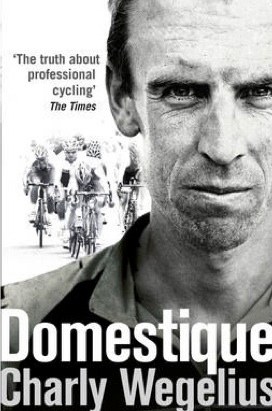

The Cyclist’s Library is a collection of books housed in our Campanet Villa, which you can read while on holiday with us. From time to time I post a review of some of the books in the library; this one is of Charly Wegelius’ autobiography: Domestique.

Charly Wegelius’ book Domestique is perhaps unique among cycling autobiographies I’ve read. For starters it isn’t an autobiography, as I discovered about ¾ of the way through. It’s a biography of Charly Wegelius, written by the cyclist Tom Southam (a rider who features in one of the key events of the tale). Perhaps there’s not a sharp line between biography and autobiography (many autobiographies of cyclists are ghost-written) and this book is in that penumbral zone. One thing is for sure though, Tom Southam has outdone all the ghostwriters I’ve read: this book doesn’t feel ghost-written. It feels like an autobiography where the writer really has got himself down on the page in full.

Charly Wegelius’ book Domestique is perhaps unique among cycling autobiographies I’ve read. For starters it isn’t an autobiography, as I discovered about ¾ of the way through. It’s a biography of Charly Wegelius, written by the cyclist Tom Southam (a rider who features in one of the key events of the tale). Perhaps there’s not a sharp line between biography and autobiography (many autobiographies of cyclists are ghost-written) and this book is in that penumbral zone. One thing is for sure though, Tom Southam has outdone all the ghostwriters I’ve read: this book doesn’t feel ghost-written. It feels like an autobiography where the writer really has got himself down on the page in full.

Not really being an autobiography isn’t what makes this autobiography unique, though. I sometimes feel that cyclists could all happily start their autobiographies the way the philosopher Rousseau’s starts his (The Confessions): “I have begun a work which is without precedent, whose accomplishment will have no imitator. I propose to set before my fellow mortals a man in all the truth of nature; and this man shall be myself. I have studied mankind and I know my own heart; I am not made like any one I have been acquainted with, perhaps like no one on existence; if not better, I at least claim originality, and whether nature acted rightly or wrongly in destroying the mold in whichever she cast me, can only be decided after I have been read.” Of course, the conclusion you draw when you read this is not that Rousseau is a great man like no other, but that he’s an ego-maniac. The same applies to cyclists—one is left from their autobiographies thinking they’re ego-maniacs. But although Wegelius looks at himself and says (on p.265) that he sees ‘a self-centred, self-obsessed hypochondriac’, by the end of the book, and from the start, you feel you know that Charly Wegelius is different from other (autobiography-writing) cyclists in not being this—he’s well-balanced, thoughtful and perceptive about his sport and the lives of those taking part professionally.

Wegelius escapes appearing self-obsessed by setting out with a different aim from Rousseau: he aims not to focus on himself, but on the role he filled as a cyclist—that of the domestique. (This book is in this respect similar to The Cycling Professor, by Marco Pinotti, which seeks to describe what kind of a work-life a professional cyclist leads). Strangly, it is by trying not to write about himself, but the role, that Wegelius succeeds so well in conveying his self. Those cyclists who set out with Rousseau’s ambition succeed only in revealing a familiar type; while trying to focus on the role he played, Wegelius as an individual shines through. It’s a shame this book came out after Wegelius had retired: had I known him then as I feel I know him now I’ve read this book, I’d have followed his every up and down in each race, with the interest of one watching a friend.

Wegelius escapes appearing self-obsessed by setting out with a different aim from Rousseau: he aims not to focus on himself, but on the role he filled as a cyclist—that of the domestique. (This book is in this respect similar to The Cycling Professor, by Marco Pinotti, which seeks to describe what kind of a work-life a professional cyclist leads). Strangly, it is by trying not to write about himself, but the role, that Wegelius succeeds so well in conveying his self. Those cyclists who set out with Rousseau’s ambition succeed only in revealing a familiar type; while trying to focus on the role he played, Wegelius as an individual shines through. It’s a shame this book came out after Wegelius had retired: had I known him then as I feel I know him now I’ve read this book, I’d have followed his every up and down in each race, with the interest of one watching a friend.